Manta, Ecuador (2019)

We spent January 12 in Manta, Ecuador. Ecuador is named for the Equator, which runs right through it. Consequently, its climate is pretty much the same year round, and usually pretty hot. Manta is the fifth largest city in Ecuador and the second largest port. We visited here in 2012 and you can view that visit here:

https://baderjournal.com/2012/01/13/ecuador/

Manta produces more tuna per capita than any other city in the world. On our last visit we were fortunate enough to have a tuna boat docked next to us on which they were actively unloading their catch. It was fascinating to watch. No such luck this time, as we had tuna boats docked on the other side of our pier but no fish in sight. They were loading clean nets, though, for their next outing. The importance of tuna in this city is shown by the large statue of a tuna in the traffic circle where the pier meets the main street.

We spent most of the day on an excursion that took us to a museum of sorts and three craft workshops. The museum was mostly devoted to displays showing how the indigenous people in this area lived. This has been a thriving fishing area since about 500 A.D., but the Spanish conquistadors arrived in 1534 and within two years the indigenous population of about 20,000 had been reduced to about 50. Sadly, this is the usual story and it is not only about Spanish brutality, since the people living in America had no defense to the European diseases the Spanish unknowingly brought with them.

After the museum we drove up on a mountain to the village of El Chorrillo.

We visited a workshop there that makes sisal bags from the leaves of the Agave plant that grows in the area. There was once a thriving market for these bags, used for carrying coffee and cacao by local farmers. But the development of agribusiness and synthetic materials has undermined that. We watched them derive fibers from the Agave leaves, mainly by pulling them apart, then refine the fibers by combing them. They spin the refined fibers into thread and weave them into cloth.

We drove then to a place called Ciudad Alfaro near Montecristi. Montecristi is a mountain town just a few miles from Manta that was founded in the 16th century by refugees from Manta seeking shelter from pirate attacks on the coast. It is famous as the home of Panama hats, which are actually made here and not in Panama. They acquired the name because most international sales are made in Panama. They were popular among US gold rush prospectors who came through Panama on their way to California and with workers on the Panama Canal. Teddy Roosevelt’s photo wearing one when he visited the canal construction was widely published in the U.S. and greatly increased their popularity.

Made from the Toquilla Palm, these hats are strong, lightweight and breathable, very practical for warm weather. A well made hat can also be rolled up tight (they are often sold rolled up into a small wooden box) and will regain their shape when unrolled. They come in many grades of quality, from a standard hat for about $35 to a super fine hat that may sell for $1,000 or more.

We were told that true Panama hats are only made in Montecristi (and should say so on the inside hat band). Toquilla palm cultivation has been tried in other locations but only the ones that grow here produce the right kind of fiber. At one time there were hundreds of weavers of these hats, but the work is backbreaking and today there are fewer than 50. The pictures below show women weaving hats in the traditional way and they bend over their work like this for some four hours at a time before a break. It’s hard to imagine how they keep all of the small straw fibers sorted out, much less weave them together in tight stitches for hours on end.

Ciudad Alfaro is an area showcasing many local crafts and it has a museum and we understand that legislators sometimes convene here as well. It is high on a cliff. Eloy Alfaro was president of Ecuador for a number of years around the turn of the 20th century. He was an important reformer and is much revered. We came across a statue of him later in the heart of Manta.

Our last visit was to a tagua nut workshop. Tagua nuts come from the Ecuadorian Ivory Palm. They are brown on the surface and white inside and are very hard, almost like stone. Often called ‘vegetable ivory,” tagua nuts are carved into jewelry, figurines and buttons. At one time tagua buttons were exported worldwide and commonly used on shirts, suits and coats, but the development of good plastic buttons dried up this trade.

When we arrived at the workshop thousands of these nuts were spread out on the grounds to dry in the sun. They are so hard that our bus just drove over them without harming them.

Inside was a demonstration of how the nuts are refined and carved. The tree fruit is large and contains many nuts. One worker sliced a nut into rounds for buttons (using his bare fingers on a spinning saw) and then punched out a round button shape. Then we watched an artisan make a small rhinoceros out of a single nut, using his bare fingers (he still had all of them) to push it against a spinning saw to carve each feature. There was also an opportunity to buy some of his work (of course), much of which really was quite beautiful.

On the way back to the ship we passed a makeshift boatyard on the beach where fishing boats were being repaired. The scaffolding is bamboo, just like we saw in Hong Kong last year.

After returning to the ship we rode the shuttle bus into town to visit the craft market set up in a central square. It was bustling with vendors selling jewelry made from shells, sculptures made of tagua nuts, Panama hats, t-shirts and other crafts and souvenirs. At the back of the square was a statue of Eloy Alfaro, who we had run into earlier in Ciudad Alfaro.

Fuerte Amador, Panama (2019)

The ship was anchored near the cruise port of Fuerte Amador, comprising three islands off the coast of Panama City. We had seen the major sights of Panama City on two previous visits so we decided to tender in to Flamenco Island in Fuerte Amador and walk down the causeway to Panama City as far as the Gehry museum. You can see our visits on previous Panama City visits to the colonial city, the ruins of the original settlement, the canal observation building and other spots here:

https://baderjournal.com/2016/02/06/panama-city-panama/

https://baderjournal.com/2018/05/09/

The causeway that connects Fuerte Amador to the mainland was built with the rocks and dirt removed from the Culebra Cut when the Panama Canal was dug through the continental divide. It forms a breakwater protecting the Pacific gateway to the canal from filling up with silt. It is about three miles long.

The causeway is very nicely maintained. There is a road down the middle with pedestrian walks along side. Benches line both sides, with alternate benches facing each way. And there are a lot of very colorful flowers. Not to mention the sea views along the rocky shore on both sides.

We did not go into the museum. It’s not a typical museum with artifacts, but with exhibits explaining and promoting biodiversity. That’s a good cause, but not really something we were anxious to see. And in Panama they have an irritating practice of charging foreigners almost twice as much as locals for admission to places like this, so it would have cost more than $30 for both of us to enter. Instead, we walked around their beautiful grounds, full of colorful flowers and trees, including a humongous fig tree shooting down new trunks all around. They said these new trunks provide additional water, but also provide natural supports for spreading branches wider and wider.

A nice fellow came along and took our picture in front of the museum, after Mary had taken one of Rick. We sat down on a bench before starting back for a long look at Panama City and especially the colonial part of town. We could see the church towers in the old town clearly from where we sat.

On the walk back we saw more flowers, including blue clematis that was being grown over large metal trellises. We also saw a number of birds, including what looked like cormorants and a scary bird that looked like a vulture, with a bald red head.

As we neared Fuerte Amador we passed a facility of the Smithsonian Institution, homeboys (and girls) of ours from Washington, D.C. Its main purpose is studying marine life, but it has a wildlife center open to the public called Punta Culebra. We had a pizza at a restaurant in Fuerte Amador then caught the tender back to the ship.

Tonight was Panama Hat night, when HAL gives everyone a hat to wear to dinner. Amazingly, this year’s hat fit Rick (they are usually way too small) and the hats for the women were unusually nice. Of course the ship’s penguins were fully dressed for the occasion.

Panama City glowed white in the late afternoon light as the ship prepared to depart. We also took a last look at Fuerte Amador in the setting sun.

Panama Canal (2019)

We approached the entrance to the Panama Canal just before sunrise on January 9. This was our fourth trip through the canal, which is always interesting even if not as thrilling as the first time through. You can see the pictures and commentary from our earlier visits here:

https://baderjournal.com/2012/01/11/panama-canal-2-2/

https://baderjournal.com/2016/02/04/panama-canal/

https://baderjournal.com/2018/05/06/panama-canal-3/

There is a lot of commentary about the canal and its history in the prior postings, which we will try to avoid repeating too much here. The Gatun locks take the ship up 3 levels in a row from the Caribbean side. It’s always a nice view in the early morning light, but unfortunately this time it was raining off and on.

HAL serves “Panama Rolls” on deck as we enter the canal (they often turn up under different names, like “Waitangi Rolls”, when we have an interesting sail-in). We had one, but then went to breakfast while in the locks. Afterward we passed the Gatun control building and exited the upper locks into Gatun Lake. The “mules,” metal cars on rails, attach ropes to the ship & are responsible for ensuring the ship doesn’t touch the canal walls, which are very close.

The lock doors have walkways at the top, permitting workers to go from one side to the other. A horn sounds before the doors open so they will know not to venture across.

A good part of the day is spent traversing the lake. The lake was created during the building of the canal by diverting a river. The canal’s locks have no pumps to move the water in and out, it is all done by gravity and very clever engineering that directs the natural water flow from higher ground. The water in the locks is fresh water from the lake and river, not salt water from the sea. The shore around the lake and on the islands is dense rain forest.

At lunch we noticed for the first time some food sculptures. Always fun, we hadn’t seen these since the last time we were on Prinsendam in 2013.

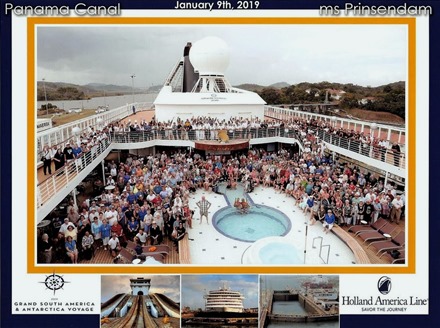

During the afternoon HAL organized a group picture to commemorate Prinsendam’s final transit through the canal. We were there, but finding us is a little like “Where’s Waldo,” only harder. Can you find us? Hint: we are not far from the upper right corner of the swimming pool area. Everybody received a complimentary copy of the photo.

The hardest part of digging the canal was cutting through the rocky continental divide. This area is called the Culebra Cut, and it cost a number of lives to dynamite it away. The sides are terraced in a number of places, partly to discourage erosion most likely, but also representing the levels where trucks were driven in to carry away the rock after it was blown up. Erosion is a continuing problem here; we were told that they have planted grass imported from Vietnam that has particularly good root systems for stabilizing the hillsides. We passed under the Centennial Bridge & headed for the Pedro Miguel locks that begin the descent toward the Pacific Ocean.

As we approached Pedro Miguel a train passed on the left. The train traverses Panama between the seas as well. It was built to accommodate travelers heading from the Atlantic coast to the California Gold Rush. Even today some companies find it cheaper or easier to unload cargo onto the train and load it onto another ship when it reaches the opposite side. The cost of sailing through the canal is substantial and based upon the size of the ship. We have heard of large ships having to pay Well over a million dollars to cross, and it has to be a cash transaction. A ship cannot enter the canal until the money has been transferred.

At Pedro Miguel the ship throws a rope down to a couple of guys in a rowboat, who connect it to a rope from a mule that they have brought out with them. On the other side the ship is close enough to throw the rope directly to the workers on the canal wall. We were told that they tried some higher tech methods to attach the ropes but none of them worked as well as two guys in a rowboat.

Flags were at half mast because it was Martyrs’ Day, a national holiday honoring several students who were killed in a protest of American occupation of the Canal Zone some 50 years ago. On the right we could see a Super Panamax ship traversing the new locks just opened a couple of years ago. The new set of locks were built because the larger modern ships wouldn’t fit through the existing locks.

At the last set of locks, called Miraflores, is an observation building containing a museum. It has several levels of viewing platforms where you can watch ships coming through the locks. It is always crowded with onlookers waving and taking pictures of the ship. This is quite a welcome and was rather a surprise the first time we came through here. We also caught our first glimpse of the white towers of Panama city on the other side of the hills lining the canal.

We came out of the locks and sailed under the Pan American Bridge, part of the Pan American Highway that stretches from Alaska to Patagonia. The container cranes of Balboa port are near the bridge. We sailed out toward the Pacific Ocean, passing the brightly colored Biodiversity Museum, designed by American architect Frank Gehry about ten years ago. We sailed around to our anchorage on the other side, where we had a full view of the startling expanse of white skyscrapers along the shoreline of Panama City. If they were green you might think this was the Emerald City.

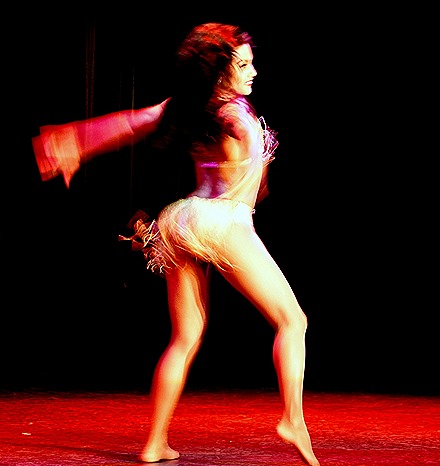

After dinner there was a performance of Colombian songs & dances by the Colombian ambassadors who had been on board since Ft Lauderdale. It was a rousing show, with very professional dancers & an excellent singer. Not all of the ambassador groups we have seen are such professional performers.

We ended the day with a view of Panama City at night. This was a very full day & the canal is always interesting. Of course, there was a towel animal. And here is a picture of where we sleep (and where the towel animals appear each night).

San Blas Islands, Panama (2019)

We arrived at our anchorage in the San Blas archipelago around noon on January 8. There are some 375 islands, give or take a few depending on your source, fewer than 50 of which are inhabited by the Kuna people. They are an indigenous tribe who apparently originated in the mountains near Santa Marta, fled from there when the Spanish arrived and settled on these islands in the mid 19th century. Today rising seas are threatening to submerge these very low islands and some of the Kuna have already begun preparing to escape to the nearby mainland. The large mountains you can see in some of these pictures are on the coast of Panama.

The night before we arrived here was Tropical Night in the dining room. The large stuffed penguins who had been lined up to greet us as we boarded the ship were stylishly outfitted for the occasion. These pictures were taken in the morning; by the end of dinner one penguin was missing from each tableaux, presumably kidnapped to someone’s stateroom. We hope they will be recovered soon.

There are something over 60,000 Kuna, about half of whom live on the islands or the nearby coast. They have been recognized as an autonomous region within Panama since 1938, after an attempt by Panama to subdue the Kuna was fought off in 1925. The Kuna celebrate this defeat of the Panamanians every year, although we have read that the Americans helped end the conflict because of their concern for stability in the area of the Panama Canal. The Kuna are traditionally a matriarchal society, with inheritance passing through mothers and men moving to their brides’ houses when they marry, but this is apparently fading in recent years.

Early in the afternoon we tendered to one of the larger inhabited islands in the Carti group in the western part of the archipelago. The Kuna were unreceptive to visitors until 10 or 15 years ago, but now permit them, including many from cruise ships. We disembarked onto a small wooden pier and walked into the small town. The island appears to be very crowded with small wooden houses & we saw no expansive open places. The narrow pedestrian streets end at the water & you can see other islands the appear very close, but these few open spaces are very trashy if you step back a few paces. One tree we walked under was hosting a green parrot & another very noisy bird.

The main street was completely lined with women selling molas. If you don’t know what that is, a mola is a picture made of a stack of different colored cloth, which are cut down to different levels to form pictures or designs. The edges are sown down & there is often applique and/or embroidery added to complete the picture. They often depict birds, animals, fish or insects worked into extremely colorful designs. Sometimes more modern items find their way into a mola; we have one at home depicting teeth being extracted with pliers that was given to Rick’s father, a dentist. While the buildings were small and basic, with metal or palm leaf roofs, the island has electricity and solar panels and satellite dishes were plentiful.

The traditional dress of the Kuna women involves a lot of molas, with head scarves & arm and leg covers usually made of molas or beads.

We tendered back to the ship, where we had lunch and took a last look at the islands, much brighter in the afternoon sun. We aren’t sure which of these pictures are of the island we visited, as there were several that could be seen fairly close together. This was an interesting place to visit, but it looks like a challenging place to live.

Santa Marta, Colombia (2019)

On January 7, after two sea days, we reached our first port on this voyage, Santa Marta, Colombia. This is the oldest city in Colombia, founded in 1525, and is most famous as the place where Simon Bolivar died. It is a busy container and coal port & something of a seaside resort for Colombians.

Under our veranda this morning some crew were working on top of one of the tenders, a job I don’t think I would want.

After breakfast in the dining room (they make particularly good french toast) we left the ship. As we have often seen, there was a group of Colombian dancers to greet us on the pier.

Walking through industrial ports is often forbidden, so we boarded a shuttle to take us through the maze of stacked containers to the port gate. A madonna statue (the original, not the singer) watches over the port.

Leaving the port, we walked a little way up the Malecon, a road that follows the shore. We came upon a notable 1928 sculpture of the Spanish Conquistador Rodrigo de Bastidas, who discovered the Bay of Santa Marta in 1501 & founded the city in 1524. He stands atop a tall pedestal with a small plaza below surrounded by stone balustrades.

Across the street we found the Biblioteca Gabriel Garcia Marquez (sponsored by Colombia’s Central Bank). Nobel laureate Garcia Marquez was a local boy, having been born about 50 miles away in a small town called Aracataca that was the inspiration for Macondo in his masterpiece, “One Hundred Years Of Solitude.” A timeline of his life is painted on the wall under the name of the building.

In front of the library is the Plaza de Bolivar. It is lush with trees, with an equestrian statue of Simon Bolivar in the center. Unfortunately he is looking away from the sun (what poor planning), so it is tough to get a decent picture of him. At the end of the plaza is a white fountain with heads whose mouths would spout water if it were working, which it wasn’t.

Nearby is the Antiguo Palacio Consistorial, originally built in the 17th century but restored and updated several times since. Apparently most of the old buildings along the west coast of South America have been rebuilt several times over the years because of earthquake damage. The western edge of the volcanic Ring of Fire follows the coast of South America, leading to relatively frequent earthquakes. Anyway, today this impressive building serves as the city hall of Santa Marta.

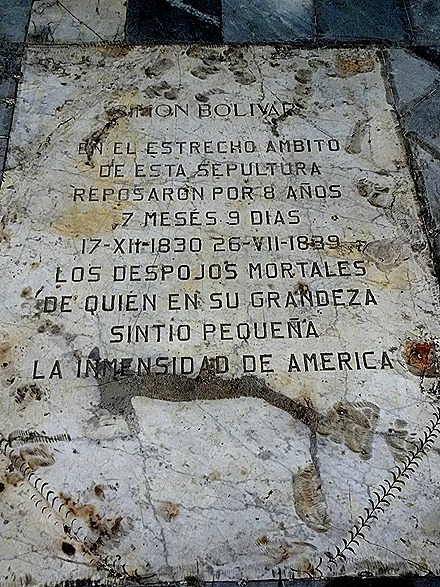

We walked on to the Cathedral, a rather plain whitewashed building, small for a cathedral. Originally built in the second half of the 18th century, it is the oldest cathedral in South America. The Christmas display was still there, complete with a lamp post carrying a sign “Let it snow.” Since it is January and it was 88 degrees out, it seems doubtful that snow has ever been part of the Christmas celebration here.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s parents were married in this church. When Simon Bolivar died in Santa Marta in 1830 he was interred here until 1842, when his remains were moved to his home town of Caracas, Venezuela. Legend has it that his heart was left somewhere in the walls here. We saw three plaques dedicated to Bolivar in the cathedral, but they were in Spanish so we aren’t sure which one marks the spot where he was interred. Also here is the tomb of Rodrigo de Bastidas, who died in Cuba in 1827, just two years after founding Santa Marta. His remains were brought here in the 1950’s and placed in an elaborate tomb.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s parents were married in this church. When Simon Bolivar died in Santa Marta in 1830 he was interred here until 1842, when his remains were moved to his home town of Caracas, Venezuela. Legend has it that his heart was left somewhere in the walls here. We saw three plaques dedicated to Bolivar in the cathedral, but they were in Spanish so we aren’t sure which one marks the spot where he was interred. Also here is the tomb of Rodrigo de Bastidas, who died in Cuba in 1827, just two years after founding Santa Marta. His remains were brought here in the 1950’s and placed in an elaborate tomb.

Across the plaza is the 18th century building that was originally the Episcopal Palace, and is now back in the hands of the church after serving in several different secular roles.

We walked on to the Parque de los Novios (Park of the Newlyweds) whose official name is Parque Santander. Francisco Paulo de Santander, whose statue graces the park, was an important associate (and sometimes antagonist) of Simon Bolivar. The area around the park must be jumping after dark as it is full of clubs and restaurants with outdoor seating among the flowers. A town festival had just ended and we saw colorful signs for it in this park and elsewhere.

We walked over to visit one more church, the Iglesias de San Francisco de Asis, passing a very impressive piece of wall art. Originally completed at the end of the 16th century, it was used in the mid 17th century as a jail by pirates (apparently Santa Marta was subject to a number of pirate attacks in that period). It has been rebuilt several times after disasters, most recently in the 1960’s. Only the façade remains of the colonial structure. A mass was in progress when we visited, accompanied by a singer playing a guitar, although since we could not see him it might have been a recording.

We saved for last the Casa de la Aduana, which is also the Museo del Oro (gold museum). The oldest building in town, this is where Simon Bolivar lay in state after he died in Santa Marta in 1830. It also houses a very fine collection of pre-Columbian art and artifacts from the Tairona and other indigenous tribes that lived in the area. Unfortunately, visiting this last proved a poor strategy, because we had barely looked at the first two rooms of artifacts before they began to close the museum. The museum is normally closed on Mondays but they had opened it just for the morning presumably because of the presence of a cruise ship. So we would have been better off visiting here first. Live and learn.

It was mid day so we walked all the way up the Malecon looking for a likely place to eat, but we didn’t find anything enticing. So we crossed the street and walked back toward the port on the bay side. There were a number of public statues of Indians, interesting if not great art. There was a row of cabanas and a lot of people swimming by the beach. We probably wouldn’t want to swim there since it is part of a commercial port, so how clean can the water be? Then there was a long row of vendors’ tents, mostly selling souvenir knick knacks.

Back on the ship as we waited to sail away there was much to see. The nearby hills were covered with cactus as big as the trees.

A lot of pelicans were flying and floating in the area. A large flock of them was perched in some trees on a hillside.

Meanwhile, up by the Lido pool there was a Colombian dancing performance. A group of Colombian “ambassadors” had been on board since we left, giving cultural classes and demonstrations. Mary came down to tell Rick about it, but he only made it up for the tail end of their dance. More about them in a future episode.

So as the sun set we sailed away from Santa Marta, our first port in South America.